On Thursday 9th November the History Society heard a lively and informative talk by Tony Hadland on “Steam and Steel in the Vale of the White Horse”.

Mr Hadland described in detail the history of two enterprises, beneficiaries of the Industrial Revolution, that at first manufactured farm equipment, but then went on to diversify into other spheres. He also described the history of the Wantage Tramway, that emerged later.

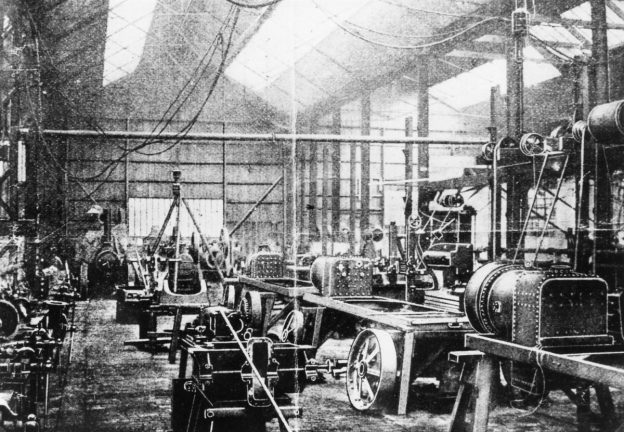

Tony Hadland’s first enterprise was Wantage Engineering, started by John Austin, that made small-scale farm equipment. Its development was affected by the Swing Riots in 1830, that started in Hungerford but spread to Wantage, and the foundry was attacked and damaged by the rioters. Arrests were made, and the prisoners sent to Abingdon Gaol, but later set free. The foundry recovered, and continued making farm machinery, including Ploughs, Threshers, Winnowing and Dressing machines, and also traction engines. By 1858 60 men were employed

there, and in 1860 they had developed a steam engine that could connect in the fields with Threshers. They were now exporting to many countries in Europe, including Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. By the end of the century, they were exporting to places like Argentina, Australia and Malaya.

In 1900 the Company was bought by Lord Wantage, who had been MP for Berkshire for 20 years, and Lord Lieutenant for 15. He had been one of the Founders of the British Red Cross Society, and a major contributor to the Wantage Tramway Company. This helped the

Company to continue, and production was greatly increased. At this time they developed a mobile electricity generator, which was very advanced for its time. When Lord Wantage died, the Company continued to be assisted by his Widow, Lady Wantage. They developed

further during WW1 when they were converted to munitions, and on to WW2, when they contributed to the manufacture of the Bouncing Bomb. After the War the firm continued with high precision milling, and work for the nuclear industry. Traction engines continued to attract the public’s interest, and one such engine, named “Constance”, used to be seen frequently at rallies around the country.

The second Company described by Tony Hadland was Nalder & Nalder. Based in East Challow, this company was founded by the Nalder Brothers, making use of the Wilts & Berks canal to transport goods and machinery. They began in about 1857 in a ramshackle building behind a

bpub, the Goodlake Arms. Like the previous company they specialised at first in manufacture of farm machinery, in particular in dressing and grading grain, but also in threshing machines and traction engines. But by dint of clever advertising and strong local support their growth was

rapid. By 1903 they employed 150 men, and were exporting widely. Many medals were won over the years. By the 20th century they had also diversified into food and drink production, especially into cocoa and coffee products. The company enjoyed the support of many local people, and built a housing estate for their employees.

They were also instrumental in helping to fund the third enterprise dealt with by Tony Harland, the Wantage Tramway. This was formed in 1873 to link Wantage with its railway station. It was part of a plan to cover Berkshire with a network of trams. It opened in 1875, and at first it was

horse-drawn, but quickly converted to steam. It was popular, but very slow, and could not compete with the motor car which was fast developing in the later years. It closed to public use in 1925, then to freight in 1945. The most famous locomotive, called ‘Jane’, or ‘Shannon’, still exists, and can now be found in Didcot Railway Museum.